A Tribute to the Black Voices that Made Modern Music

The Museum at Bethel Woods Assistant Curator Julia Fell explores the contribution of Black musicians and how it continues to influence the music scene today.

When remembering Woodstock, it is important to not separate the seminal cultural event from its diverse cultural influences, notably from the Black music traditions that shaped not only the social climate of the summer of ’69, but the music itself.

We recall the 1960s as a decade of breakthroughs in equality and progressivism. The Civil Rights Movement worked to counter systemic racism and segregation through the ’50s and ’60s. However, the bombastic clashes between Civil Rights activists and law enforcement often drown out the equally important cultural influences of Black culture on mainstream American society. In romanticizing the counterculture and its music, much has been forgotten or ignored.

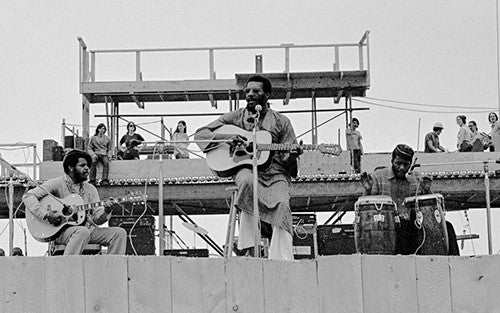

Despite organizers hoping for a diverse crowd, the Woodstock festival goers themselves were mostly white. Of over 150 artists who graced the main stage, only about 15% were Black artists. Because of this disparity, the amount of Black influence on the festival can be easily (though not justifiably) overlooked. It is undeniable, however, that the music played throughout the festival was greatly influenced by Black music traditions.

Popular music in the United States is inherently intertwined with elements of Blackness and diverse African traditions. Dr. Steven Lewis of the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) wrote that for hundreds of years, Black Americans drew on the “ancestral connection to Africa as a source of pride and inspiration."1 Perhaps the new and unique sounds present in Black music were a major part of what has driven American popular music through its many evolutions, including the rise of the rock genre. Down to the level of the musical instrument, Black culture has had an indelible effect on American music.

For instance, the banjo (a ubiquitous instrument in American folk music) evolved from stringed instruments in West Africa. Laemouahuma Daniel Jatta, a banjo scholar from Gambia, told NPR that he believes that the modern banjo specifically evolved from the traditional akonting - a three stringed instrument.2 Over time, the instrument was adapted to conform to European tuning systems. In the modern day, the instrument is seldom associated with Black artists in popular culture, according to the NMAAHC.

On the Woodstock stage, traditional African drums made an appearance during Jimi Hendrix’s set. Drummer Juma Sultan explained in an interview that with Jimi Hendrix’s combination of both Latin and African tastes they were able to create a “different type of sound.”

To expand on the Black influence at Woodstock, one needs only look into the artists who inspired performers on the Woodstock stage. Carlos Santana was heavily influenced by such iconic artists as B.B. King, T-Bone Walker, and John Lee Hooker, as well as his acquaintance, Miles Davis. Santana described Davis’ music as “…very dynamic, very powerful and full of fire and passion."3 Janis Joplin was inspired by many blues singers such as Bessie Smith, Odetta, Big Mama Thornton, Billie Holiday, Lead Belly, and, later in her career, Aretha Franklin, Tina Turner, and Otis Redding. Joe Cocker’s soulful performances were known to be inspired by Ray Charles.

Although these artists were vocal about drawing inspiration from the Black artists who had been changing the music scene with new and unique ideas, the truth of the matter is that while many white artists were being booked for major events, Black artists were often under-booked and under-credited. Pulling inspiration from Black artists contributed to popular mainstream music by white artists in the 1960s, but borrowing without due credit can also undermine the original contributions of Black performers, and the pride, inspiration, and history that went into the original Black songs. What was created from African pride quickly became an aesthetic listening preference for many non-Black Americans from coast to coast. Any piece inspired by such music would have the feel but lack the fundamental core that makes Black American music most special.4

The core of deeper meaning in Black music was especially evident as Richie Havens improvised his song “Freedom,” which drew heavily from an African spiritual called “Motherless Child.” African spirituals were folk songs born from the experiences of enslaved African peoples. The creation of these songs likely came naturally, as music was central to many African cultures and played roles in both every day and ritual practices.5

Black influence is so deeply ingrained in modern music that many musical genres, especially rock ’n’ roll, would not be what they are today without the inspiration of Black creators over hundreds of years. Though the appreciation of the result of this musical evolution is not in short supply, ultimately, it is important to recognize the Black influence that made the music of the 1960s and Woodstock, and continues to shape music today.

A great resource for learning more about Black influence on music is the Black Rock Coalition, a nonprofit whose mission is to document and embrace the roots of Black music through various genres and to challenge stereotypes of genres such as rock as “white music.”

Works Cited

[1] “Musical Crossroads: African American Influence on American Music.” Steven Lewis. Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. September 2016.

[2] “The Banjo’s Roots, Reconsidered”. Greg Allen. NPR. August 23, 2011.

[3] Santana Interview (video)

[4] “Why is Everyone Always Stealing Black Music?” Wesley Morris. The New York Times. August 14, 2019.

[5] “African American Spirituals”. Library of Congress.