Bill Graham and the “Chairman of the Board”: The Untold Story of B.B. King at the Fillmore

The Museum at Bethel Woods Fall Oral History Intern Will Kleffner dissects the connection between blues and rock.

You may have heard of Bill Graham, the legendary concert promoter famous for launching the careers of iconic rock groups including The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Big Brother and the Holding Company, and Santana. You’ve probably also heard of B.B. King, the massively influential blues artist. But did you know that without Graham, King’s career might have petered out by the end of the 1960s? Let’s find out what happened.

and B.B. King in 1971 (right, photographed by Heinrich Klaffs).

(Both images are available under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike

2.0 Generic license).

Bill Graham acquired the Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco, CA in 1966. The venue had previously been owned by Black entrepreneur Charles Sullivan1,2, who had already introduced many Blues and R&B acts to the Fillmore stage. Graham was a strong supporter of the rock genre, but he also had a desire to introduce his mainly white audiences to music they had likely never been exposed to. Graham proceeded to book famous R&B artists like James Brown and Aretha Franklin alongside rock performers like Chuck Berry, Santana, and The Jefferson Airplane. Then, in February of 1967, Graham booked one performance that had unforeseen benefits for a hesitant bluesman: Riley “B.B.” King.

Born in Itta Bena, Mississippi in 1925, a young B.B. King worked as a sharecropper and tractor driver until 1948, when he became a disc jockey for WDIA Radio in Memphis, Tennessee3. His career as a disc jockey propelled his performance career. He achieved his first commercial success with “Three O’Clock Blues” in 1952 and consistently found success on the R&B charts throughout the 1950s.

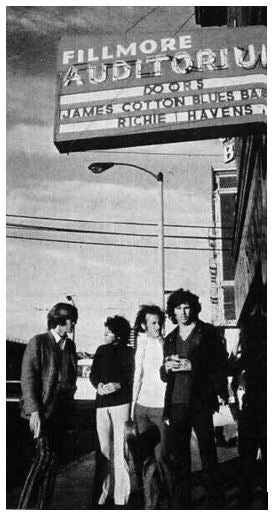

Auditorium in 1967.

Origin of photo unknown.

King had performed many times at the Fillmore Auditorium throughout that decade, playing for predominantly African American audiences. In fact, under Charles Sullivan, the venue was a regular stop on the “Chitlin Circuit,” a collection of performance spaces throughout the United States for African American performers and audiences during a period of strict segregation4.

However, by the 1960s, King’s fame was dwindling, as his music was no longer reaching its intended audience. At the height of the Civil Rights movement, many members of the black community were more attracted to the open, direct discussion of black power in the soul music of artists like James Brown and Aretha Franklin. The lyrics to King’s songs reminded these audiences of the past, a period they were trying to forget5. King often described the black community’s rejection of his music as “being black twice.”6 King was disappointed that the black community did not accept the blues, an authentically African American form of music that “followed our path from slavery to freedom.”7 In the late 1960s, Sidney Seidenberg became King’s manager and aggressively pushed him into a variety of new venues that were presenting blues music to white audiences8. As a result, B.B. King found a receptive audience in the most unexpected of groups: white hippies.

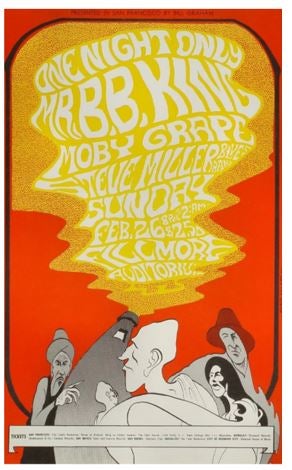

headlined the Fillmore Auditorium.

(10)

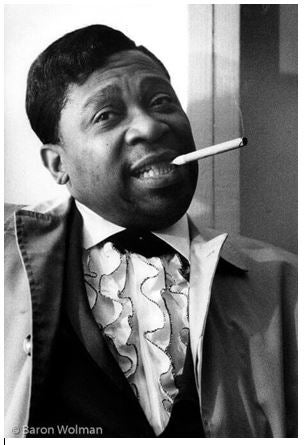

In February of 1967, Bill Graham booked B.B. King and his band to perform once again at the Fillmore Auditorium. Though in need of new fans, initially, King was hesitant to perform in front of a predominantly white audience. Graham, often described as having a personality that was a mixture between “Mother Theresa and Al Capone,”9 had a keen sense of getting what he wanted. Just before his performance at the Fillmore West, King expressed his doubts to Graham, stating that “this wasn’t the right place.” Graham assured him that it was, and King and his band prepped for the show that night.

Photo by Baron Wolman. Copyright Baron Wolman.

In true Graham fashion, he went on stage to introduce B.B. King in a way King described as the “nicest and shortest introduction” he ever received11. Graham succinctly proclaimed, “Ladies and Gentlemen, I bring you the Chairman of the Board: B.B. King!” Upon the announcement, each member of the audience (about 3,000 in total) stood up and proceeded to give King a 45-minute standing ovation. Almost immediately, King found himself overwhelmed with emotion, and certainly a bit of confusion. Reflecting on his experience, King was touched by the appreciation his audience gave him, and he was simply unsure as to how to repay them for their support12. At the time of his death, King stated that his performance at the Fillmore Auditorium in 1967 changed the trajectory of his career13.

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services with additional support from The O’Connor Foundation and Robyn Gerry. A campaign to raise funds for the current and future Fellowship is ongoing. Support Will and future opportunities by donating to Bethel Woods.

1 Joel Selvin, “A Night at the Fillmore Changed B.B. King’s Career Forever,” SFGate, May 15, 2015. https://www.sfgate.com/music/article/Music-A-night-at-the-Fillmore-chan…

2 Nicole Meldahl, “The Mysterious Death of the Mayor of the Fillmore,” California Historical Society, 2016. https://summerof.love/mysterious-death-mayor-fillmore/

3 Diane Williams, “The Life and Legacy of B.B. King: A Mississippi Blues Icon,” The History Press, 2019.

4 Diane Williams, “The Life and Legacy of B.B. King: A Mississippi Blues Icon.”

5 Ulrich Adelt, “Black, White, and Blue: Racial Politics in B.B. King’s Music from the 1960s.” Journal of popular culture 44, no. 2 (2011): 195–216.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Terence McArdle, “B.B. King, Mississippi-born master of the blues, dies at 89,” The Washington Post, May 15, 2015, accessed November 27, 2021.

9 Ben Marks, “Bill Graham and the Rock and Roll Revolution Arrives in San Francisco,” TRPS.org, accessed on November 29, 2021.

10 John H. Meyers, “BG052-PO,” Feb. 26 1967. https://www.wolfgangs.com/posters/b-b-king/poster/BG052.html

11 Ulrich Adelt, “Black, White, and Blue: Racial Politics in B.B. King’s Music from the 1960s

12 Ibid

13 Joel Selvin, “A Night at the Fillmore Changed B.B. King’s Career Forever,” May 15, 2015, accessed November 28, 2021.