Country Joe McDonald, lead singer of the psychedelic rock band Country Joe & The Fish, wasn’t supposed to perform at Woodstock as a solo act, but on Saturday afternoon, while the stage was being set for Santana to perform, he was asked to fill some time and keep the audience entertained. What he did on stage became an important part of the Woodstock legacy and the beginning of the next phase of Joe’s career.

Day Two, Performer 2: Country Joe McDonald

Performed Saturday afternoon, August 16, 1:00–1:30 pm

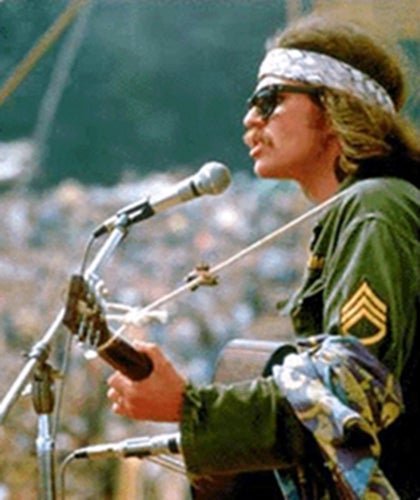

Country Joe McDonald opening his solo set on the second day of the Woodstock festival.

Country Joe McDonald: guitar, vocals

Country Joe McDonald's Woodstock Setlist

- Janis

- Donovan's Reef

- Heartaches by the Number

- Ring of Fire

- Tennessee Stud

- Rockin' Round the World

- Flying High

- I Seen a Rocket

- The "Fish" Cheer/I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die Rag

Born in Washington, D.C. at the dawn of World War II, Joseph Allen McDonald grew up in the Los Angeles suburb of El Monte, California. Joe was raised in a left-leaning household (his parents had once been card-carrying Communists, and they named him after Joseph Stalin). His early and frequent contact with political activity in support of labor unions, farmworkers, and other leftist and progressive causes shaped his ideas and actions for the rest of his life. Although neither parent was particularly musical, Joe was also exposed to myriad musical styles in Southern California, playing trombone in jazz bands in high school and guitar in various folk groups. Then, after he graduated from high school, Joe joined the U.S. Navy.

In 1962, McDonald was out of the Navy and back in Southern California. He lived with various family members while attending Mt. San Antonio Junior College and L.A. State College. It was there that he met future collaborator Blair Hardman, started a radical magazine called Et Tu, and married his first wife, Kathe Werum. By 1965, McDonald got the itch to move to Berkeley, ostensibly to study at U.C. Berkeley, and he split his time between music and political activism. Before leaving Los Angeles, he and Blair Hardman recorded an unreleased album of original music and covers of Bob Dylan, Tom Paxton, and traditional songs titled The Goodbye Blues.

In Berkeley, McDonald immersed himself in the city’s folk music scene, playing mostly solo gigs, playing Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Lee Hays, and his own material. Soon, he was regularly performing with two groups: The Berkeley String Quartet and The Instant Action Jug Band. Future bandmate Barry Melton was also an occasional Instant Action performer. McDonald was involved in the growing Free Speech Movement, advocating for the elimination of R.O.T.C. from the Berkeley campus and other causes, and he created a new magazine about the San Francisco Area folk scene called Rag Baby. A dearth of articles for one particular issue prompted McDonald to record a four-song promotional EP and sell the issue as a “talking issue.” The resulting EP, Rag Baby Talking Issue No. 1, included two songs by McDonald and two by Peter Krug. The lineup for McDonald’s songs included Joe on harmonica, acoustic guitar, and vocals, Barry Melton on vocals and electric guitar, Carl Shrager on washboard and kazoo, Bill Steele on washtub bass, and Mike Beardslee on vocals. For the EP, this quasi-jug-band needed a name, and Ed Denson (later manager of the band) suggested “Country Joe & the Fish.” While stories vary as to the origins of the band’s name, Ed quoted Mao Tse-Tung, who referred to revolutionaries as “the fish who swim in the sea of the people.” The “Country Joe” part of the name obviously refers to McDonald, but it was also Joseph Stalin’s nickname, a convenient double meaning. The first incarnation of Country Joe & the Fish was born, and the EP contained the first recording of the song that they will always be identified with, “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag.”

Band members came and went, a second promotional EP was released by Rag Baby Records, and Country Joe & the Fish landed a record deal, releasing four albums leading up to the summer of 1969. McDonald was growing dissatisfied with the direction of the group, even leaving for a time, and by the time of the Woodstock festival in August 1969, only McDonald and Barry Melton remained from the “classic” Country Joe & the Fish lineup. It almost seems like fate that Country Joe McDonald would get his big solo break at Woodstock.

McDonald had arrived at the festival on Thursday, the day before it was to start. He wanted to see the whole three days of music performances. In a recent interview, he said, “I always like to hear the other bands playing as I learn new things from them. I saw lots of the acts at Monterey and Woodstock and enjoyed myself very much.” On Saturday, he was sitting on the side of the stage when festival producer John Morris asked if he would fill in some time with an acoustic set while Santana’s equipment was being set up. He reluctantly agreed, and someone found him a guitar and a rope to use as a strap. Chip Monck introduced his “very fond friend, Mr. Joe McDonald,” and McDonald walked out to the microphone wearing a green Army shirt with sergeant stripes and a name strip that read “EVERETT.” A scarf was tied around his left arm and another around his head above his dark sunglasses.

After greeting the audience and asking them if they were “having a good time,” he began his nine-song set with “Janis,” a song he had written two years earlier at the request of his former girlfriend Janis Joplin. The song, which appeared on the second Country Joe & the Fish album, I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-To-Die, was an odd choice for the first of the set; its slow pace and slightly atonal chord changes make the melody difficult for some listeners to appreciate. The audience gave him polite applause. He followed with “Donovan’s Reef” from the band’s fourth album, Here We Are Again, and three country standards: “Heartaches by the Number” (by Ray Price and Vince Gill), “Ring of Fire” (by June Carter and Merle Kilgore), and “Tennessee Stud” (by Jimmie Driftwood), all of which would appear on his second solo album, Tonight I’m Singing Just For You, the following year.

After the three country songs, McDonald played “Rockin’ Round the World” from the yet-to-be-released final Country Joe & the Fish album, CJ Fish, and “Flying High” from their first album. He closed his set with “I Seen a Rocket,” which was later released as a single. By this time in the set, McDonald appeared more into his performance, and the upbeat, fun songs should have elicited more reaction from the audience than they did.

McDonald was disheartened by the poor audience response to his acoustic set, so he walked off stage and asked his tour manager if it would be alright to play “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag” as an encore, since it was already planned that he would perform the song with Country Joe & the Fish on day three of the festival. As Joe tells the story, the road manager replied, “Nobody’s listening to you, so what difference does it make?” He returned to the microphone and started his famous (infamous) cheerleader call-and-response: “Gimme an F! Gimme a U! Gimme a C! Gimme a K! What’s that spell? What’s that spell? What’s that spell? What’s that spell?” to which the audience rose to their feet and told the pro-war world to get screwed. McDonald’s anti-war satire, “Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin-To-Die-Rag,” which followed the “FISH Cheer” had the audience singing and clapping along. At that moment, especially after the release of the Woodstock movie and soundtrack, Country Joe McDonald had “a solo career and a solo identity,” and young people around the world, including the troops in Vietnam, had an anti-war anthem. Filmmaker Michael Wadleigh captured the sing-along moment in the Woodstock movie by adding the lyrics as subtitles, complete with the follow-along “bouncing ball.”

Soon after Woodstock, Country Joe & the Fish disbanded. Joe released his first solo album, Thinking of Woody Guthrie, in December 1969. He had recorded it quickly in Nashville, and he used the remaining studio time to record a collection of country-influenced songs for his wife, released the following March as Tonight I’m Singing Just for You. Joe also continued his political activism, lending his support to demonstrations and benefits and participating in the F.T.A. Show (F*** the Army), landing him on President Richard Nixon’s “enemies list.” He released Resist! Sings Country Joe on his Rag Baby record label in 1971.

Country Joe McDonald's debut solo album, Thinking of Woody Guthrie (Vanguard, 1969) was a collection of songs by one of his musical heroes. His second solo album, Tonight I'm Singing Just for You (Vanguard, 1970), was dedicated to his wife.

In 1979, he and Bill Belmont restarted the label, which has released several of his and other artists’ albums and is still active today. He released two albums a year and appeared in three movies through the 1970s, and continued releasing an album every year or two in the 1980s, ’90s, and 2000s. In 2017, Joe released his 36th solo album, simply titled 50.

Country Joe McDonald is still writing, performing, and releasing new music fifty years after the first Country Joe and the Fish album. His latest CD is titled 50 (Rag Baby, 2017).

Country Joe McDonald has been married four times and has five children. He is still committed to political activism for such causes as saving the whales, and protesting U.S. involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan. The author of a 2017 article stated, “More importantly, he was one of the first of the Bay Area musicians to take an active role spotlighting the plight of returning soldiers and demand they be treated with compassion, at a time of great political and social confusion. For all intents and purposes, no musician has been more relentlessly supportive of Vietnam Veterans than Country Joe McDonald.” About his ongoing legacy, McDonald said, “My goal will never be achieved in my lifetime, of peace and love on the Planet Earth, but I’ll do my bit to further it as long as I can, and when I’m gone, someone else will pick it up and that’s the way it will go. It will be known that I contributed my part, as to the music and the culture of my generation, not just politically, although I added a political, social, moral element when there wasn’t one.”

—Wade Lawrence & Scott Parker