Hippies in the Heart of Dixie: The Atlanta International Pop Festival 1969

Fall Oral History Intern Jarrett Hill discusses the often-overlooked Atlanta International Pop Festival and its ties to Woodstock.

Festivalgoers were pressed for space on the Atlanta

International Raceway.

Temperatures rose to triple digits as the fire department attached sprinkler heads to their hoses in an attempt to cool off the sea of Southerners before them. Some people found shelter under nearby pecan trees, working with friends and strangers alike to tie tapestries, tents, and any other shade together. In one review of the event, the crowd in such heat was compared to the sea of embattled soldiers waiting at the railroad yard in Gone With the Wind. [1] Watermelon rinds, having sustained people long after the concessions ran out, scattered the grounds of the Atlanta International Raceway, their sweet juices mixing with the dusty Georgia red clay that coated everything. Yet despite these conditions, spirits ran high. People’s favorite bands played for hours at a time, and a vibrant, proud community was forming.

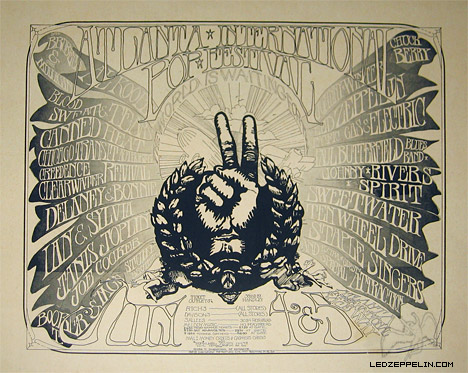

Advertised as “the biggest event of its kind that the Deep South has ever seen” and promising everything from flowers to karate exhibitions to palm readers– this was the 1969 Atlanta International Pop Festival. [2]

including the psychedelic bright yellow and red standards.

Image source: https://tinyurl.com/ms7h7h67

It is important to clarify that this was the first Atlanta International Pop Festival (also known as Atlanta Pop), held on July 4 and 5, 1969, at the Atlanta International Raceway in Hampton, GA. The second Atlanta Pop in 1970 is much more well-known as a descendant of Woodstock (even copying Woodstock’s slogan of “three days of peace, love, and music”), but the first instance of the festival plays an unsung role in American countercultural history.

Held only two months before the festival in Bethel, 1969’s Atlanta Pop can be seen as the last rest stop on the long road to Woodstock, with a significant number of the now-iconic performers also playing, including Joe Cocker, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Janis Joplin, and the group widely considered the highlight of Atlanta Pop— Sweetwater. And while Atlanta Pop is, almost without fail, discussed with Woodstock, it stands on its own as a significant event in the cultural history of the Southeastern United States.

Sweetwater’s performance.

Image source: http://www.thestripproject.com/atlanta-pop-festival-1969/

A strong anti-hippie sentiment existed in the Southeast then, and Atlanta Pop was expected to strike this nerve – and to some extent, it did. One attendee recounts looking for local food vendors after realizing festival concessions had run out and finding “No Hippies Allowed” signs posted in many restaurant windows. [3] Georgia’s staunchly segregationist governor, Lester Maddox, is widely quoted as saying the event was “one of the worst blights that ever struck our state.”[4] Maddox and his supporters may have feared an unprecedented gathering of anti-war individuals, or that “politics” would take over Atlanta’s Independence Day weekend.

Part of those “politics” would have included a major festival uplifting black art and artists. Atlanta has been called “the blackest city in America.” At a time in American history when the wants of black Americans could no longer be ignored by the white populace that controlled the culture (and counterculture), Atlanta Pop attempted to advertise to the South’s black music lovers as well. Advertisements and press releases for the festival state that soul, blues, and jazz would be just as present as the psychedelic and rock music traditionally associated with the counterculture. Major black artists, like Chuck Berry and The Staples Singers, were signed alongside Janis Joplin and Led Zeppelin.

The organizers of Atlanta Pop were well aware of the Southeast’s socially conservative atmosphere. Yet, they saw the successes of the few pop festivals that had sprung up in the South over the previous year and felt emboldened. Organizer Robin Cornant stated that, after seeing the success of December 1968’s Miami Pop Festival, he thought: “If it can happen there, it can happen here.”[5] Despite the expectation of some resistance, Atlanta hippies, coming both from city hubs like Peachtree and 10th St. as well as metro towns like the Allman Brothers’ home of Macon, showed up.[6] Many people from other countercultural hubs of the Southeast came to Atlanta Pop, such as Starman, a hippie who had become a local legend in Miami for his eccentric dress and the metal stars he crafted and distributed at both Miami and Atlanta International Pop.[7]

Despite the harsh conditions of the Georgia summer, the festival opened in good spirits and maintained those feelings throughout much of the weekend. Even the local reporting found the event unexpectedly positive– the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, almost incredulously, reported: “Music Fans Stay Orderly Despite Heat, Wine, Drugs.”[8] For one of the first times, those who considered themselves countercultural found a community in the South and could see just how many people there were who thought as they did. That is of undeniable importance and is likely one of the main reasons this event is so fondly remembered by attendees today.

Of course, not everyone agreed, and some could not get past the idea of charging for admission to such a harsh physical environment. In addition, some hippies were upset with the commercialization of music and hippie values, resulting in the organizers putting on several subsequent free concert performances from festival groups (in addition to the Grateful Dead).

How did the “blackest city in America” receive a festival that, while attempting to market to black Americans alongside hippies, only featured four bands with black musicians out of the 22 that performed? The response was mixed— as one reporter bluntly put it, “Twelve hours of white rock got a little boring.”[9] Many of the white bands pulled extensively from genres that developed out of black traditions and communities, such as gospel, funk, blues, and R&B. The black newspaper The Atlanta Inquirer noted this, stating that some of the white performers played “a few borrowed [songs]” and performed “with an accent on blues.” [10] And, to many people’s chagrin, Chuck Berry, the “Father of Rock and Roll” advertised on the event poster, never performed.

That being said, some of the joys of Atlanta Pop came through for many black attendees, too. One countercultural and civil rights magazine, visiting from Jackson, Mississippi, noted many of the logistical issues of the festival yet lauded “the youth of the South’s immense love of music,” on display for the world to see. [11] In addition, two groups of black or integrated musicians were universally uplifted as festival standouts — Sweetwater and The Staples Singers.

Much like at Woodstock, performances went well over schedule, extending each day for over 16 hours straight. And also, like Woodstock, politics were critical to Atlanta Pop, just as Governor Maddox feared. Sweetwater flew a United Farmworkers flag on stage during their set. At the same time, civil rights groups such as the Southern Student Organizing Committee took an interest in this countercultural event “in the heart of Dixie.” When the festival was reprised the following year, Jimi Hendrix ended his set and introduced a fireworks show with his Star-Spangled Banner, made famous in Bethel the year prior. So why is the first Atlanta Pop barely remembered, while Woodstock is a generation-defining event?

For attendees of the festival, many felt it was a watershed moment. Providing a strengthened sense of liberation from the social atmosphere of the Deep South, many attendees are still incredibly proud of this home-grown event, and it was as impactful for them as the subsequent festival in Bethel, NY, was for its attendees. Atlanta Pop 1969 was a community-building event and, much like with the Woodstock Nation, the attendees felt they had formed a kinship with the thousands of people they shared the weekend with. [12]

[video clip, from 4:00 to 4:19] https://youtu.be/XXPilumTAhg?start=241&end=259

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, reflecting on the event, stated that Atlanta Pop put the South on the map of the rock music industry. Not only that but immediately after the festival, the newspaper encouraged the event to occur again, as “a full music diet is good for a city.”[13] The joy of music and community on display over Independence Day weekend, 1969, opened minds. Historian Mark Kemp, himself an attendee of the festival, stated that the festival’s greatest impact was how it showed that in the American South, which outsiders viewed as closed-minded, the hippie movement had flourished. “We may have felt like freaks, but now we know we weren’t the only freaks.”[14]

[1] “The Atlanta International Pop Festival,” The Kudzu (Jackson, MS), July 1969.

[2] The Atlanta International Pop Festival, “On July 4 and 5 at the Atlanta Raceway,” advertisement. https://www.ledzeppelin.com/sites/g/files/g2000013721/files/2022-04/atl…

[3] Edmondson, Patrick, “Atlanta Pop Festival 1969,” The Strip Project (blog). February 13, 2014. http://www.thestripproject.com/atlanta-pop-festival-1969/

[4] “July 4, 1969: Atlanta International Pop Festival Rocks,” Best Classic Bands, July 4, 2015. https://bestclassicbands.com/atlanta-international-pop-festival-1969-7-…

[5] Edmondson, “Atlanta Pop Festival 1969.”

[6] Moore, Booby, “Atlanta International Pop Festival 1969, part I,” Stomp and Stammer. June 30, 2019. https://stompandstammer.com/feature-stories/atlanta-international-pop-f…

[7] Edmondson, “Atlanta Pop Festival 1969.”

[8] “Music Fans Stay Orderly Despite Heat, Wine, and Drugs,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 6, 1969.

[9] “The Atlanta International Pop Festival,” The Kudzu.

[10] Knippenberg, J. The Atlanta Inquirer, July 1969.

[11] “The Atlanta International Pop Festival,” The Kudzu.

[12] Atlanta Journal-Constitution, “A look back at the Atlanta International Pop Festival,” June 26, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XXPilumTAhg.