Tim Hardin

Tim Hardin was a respected songwriter who lived a tortured life on and off the stage. His performance on the first day of Woodstock was marred by the performer’s legendary stage fright and his debilitating addiction to heroin.

Day One, Performer 4: Tim Hardin

Performed Friday night, August 15, 8:45–9:30 pm

Tim Hardin Band Members

- Tim Hardin: vocals, guitar

- Richard Bock: cello

- Ralph Towner: guitar, piano

- Bill Chelf: piano

- Gilles Malkine: guitar

- Glen Moore: bass

- Steve "Muruga" Booker: drums

Tim Hardin Woodstock Setlist

- How Can We Hang On to a Dream?

- Susan

- If I Were a Carpenter

- Reason To Believe

- You Upset the Grace of Living When You Lie

- Speak Like a Child

- Snow White Lady

- Blues on the Ceilin'

- Simple Song of Freedom

- Misty Roses

Tim Hardin grew up in Eugene, Oregon, the son of a classical musician mother and a domineering father. A disinterested student, Hardin dropped out of high school and joined the U.S. Marines at the age of 18, where he developed his taste for heroin. Returning to Eugene for a time after he was discharged, he arrived in New York in 1961 and gravitated toward Greenwich Village, ostensibly to study at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. He was dismissed from the school and turned to music, performing mostly blues in the Village. He befriended Fred Neil ("Everybody's Talkin'"), "Mama Cass" Elliot, and John Sebastian and began writing songs tinged with despair and romanticism.

Hardin drew on his life experiences to create simple songs. In a 1968 interview, Hardin looked back, saying, "When I started, I was a terrible guitar player. Six months after I started, I was broke, so I gave lessons to college kids to make money. There are now an awful lot of very bad young guitar players around America as a result. Because of this, I started out writing my own material because I wasn't good enough to cope with anyone else's involved arrangements. That's why my songs are simple." Growing impatient, Hardin moved to Boston, where he performed his songs in small clubs. He was signed to a contract with Columbia Records and recorded a number of demos in the studio. Columbia terminated his contract less than a year later, and none of the demos were released (they would later be released as Tim Hardin 4 and This is Tim Hardin).

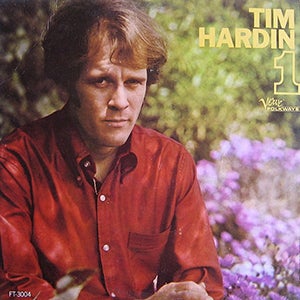

He moved again, this time to Los Angeles, where he met his future wife and muse, Susan Yardley. Returning to New York, Hardin signed with Verve Forecast and released his first album in 1966. Tim Hardin 1 was an artful mix of blues, country, rock, jazz, and ballads, including "Reason to Believe," "How Can We Hang On to a Dream?," and "Misty Roses." Critics have ranked Hardin's debut album among the most important of the era, comparing it to Dylan's Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited. He moved back to Los Angeles shortly before the debut album was released, and there he recorded the songs for his second album. Tim Hardin 2, released in 1967, contained "If I Were a Carpenter," "Red Balloon," and "Black Sheep Boy." Rocker-turned-lounge-singer Bobby Darin recorded "If I Were a Carpenter" and released his single before Hardin could release his version, and Darin's record became a huge hit. Hardin's songs were recorded by a range of artists, including Rod Stewart's recording of "Reason to Believe" and others by everyone from Joan Baez and Johnny Cash to The Carpenters, The Four Tops, Johnny Rivers, and even Robert Plant and Neil Young. But Hardin was yet to have one of his own singles make the charts.

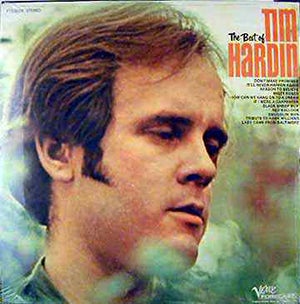

Tim Hardin was loved by the critics and admired by other performers who recorded his songs, but his extreme stage fright and addiction to heroin made him an unreliable live performer. He canceled or skipped scheduled shows, and when he did appear, he was often not fit to perform. He didn't tour to promote his second album, and in the process, he missed the career boost he would have gotten from Bobby Darin's success with his song. In early 1969, Hardin was signed to Columbia Records and released his version of Bobby Darin's "Simple Song of Freedom," which ironically would be his only charting single. Verve released The Best of Tim Hardin that year, giving many of the Woodstock festival attendees later that summer a familiarity with his songs.

Woodstock promoter Michael Lang had hoped that Woodstock would represent a comeback for Hardin but found it difficult to get the stage fright-stricken singer/songwriter onto the stage. In an effort to avoid being forced out before he was mentally prepared, Hardin reportedly got himself deeply liquored up. The ploy worked, though Hardin wasn’t exactly in the best shape by the time he walked out to begin his set around 9 pm.

Walking to the piano, Hardin tentatively picked out the first notes of “How Can We Hang On To A Dream?,” a popular song from his first album released on the Verve label two years earlier. His vocals were slurred a bit, the musical pace meandering, but slowly he managed to draw the crowd in with an atmospheric delivery and sensitive vocals. Walking to the front of the stage, acoustic guitar in hand, Hardin then read a poem dedicated to his partner Susan Moore (“Susan”), which would go on to close his album Suite for Susan Moore and Damion: We Are One, One, All in One, released the following year.

Enthusiastic applause greeted the opening of the Hardin classic “If I Were A Carpenter,” which had been a huge hit for Bobby Darin in 1966. Throughout this performance, Hardin swayed unsteadily (even bumping into his microphone a few times), off in his own world. This was followed with another solo acoustic tune, “Reason To Believe,” which would be a hit for Rod Stewart a few years later (Hardin never had much in the way of commercial success with his own recordings).

Without fanfare, a backing band was then brought onstage for the remainder of the set, including the prodigiously talented Gilles Malkine on guitar and Steve “Muruga” Booker on drums. This portion of the set started well enough with a jaunty performance of “You Upset the Grace of Living When You Lie,” the band gelling reasonably well. The pace slowed for the gentle “Speak Like a Child,” which had the audience spellbound. Despite whatever misadventures Hardin may have gotten himself into offstage, everything seemed to be clicking by this point.

So it must have seemed like the exact right time to throw everything off course. Hardin walked over to the piano, removed a piece of paper from his pocket and announced to the band that they were to play “‘Snow White Lady’…in F!” Unfortunately, this “song,” based on a poem about heroin, written by Susan Moore, was completely unknown to the band before being forced upon them on the Woodstock stage. While Hardin chanted the poem, looking for anything resembling a melody, the band flopped around attempting to make something out of nothing. It was a moment that the musicians would remember as one of total embarrassment, but by this time the audience had been won over, and was surprisingly forgiving. The set got back on track for a loose-but-right rendition of the relatively lowdown Fred Neil composition “Blues on the Ceilin’,” and Hardin got a major ovation with his closing tune, a cover of Bobby Darin’s “Simple Song Of Freedom,” which had recently been a minor hit single for the troubled folksinger.

The group was called back for an encore but was cut off by John Morris who took to the stage to warn the crowd, in very strenuous terms, about some “flat blue” tabs of LSD being distributed among the crowd. Morris, acting on some rather hysterical information given to him, informed the crowd that the acid was “poison” and threatened violence against the person who was distributing the tabs. This was a bad call on several levels—firstly, those who had taken the flat, blue acid were now being told that they’d been poisoned, the cue for a major-league freak out if ever there was one—and the threat of violence went against the spirit of the event (not that most in the crowd were bothered by that in any way). In a placating move, Hardin encored with his beautifully subtle “Misty Roses,” winding down his Woodstock adventure on a gentle note.

After Woodstock, Hardin released an experimental album of songs inspired by his wife, entitled Suite for Susan Moore and Damion: We Are One, One, All in One. The album drew mixed reviews. Continuing his endless wandering and searching, he moved to Hawaii for a time, then San Francisco, then Los Angeles, and then to Colorado. He landed in Woodstock, New York, where he stayed for a time. He canceled a scheduled European tour in support of a live album, and Verve canceled his contract. Susan, fed up by his heroin addiction, took their son and moved back to California. Hardin moved to London and registered as a drug addict so he could receive free methadone, and he split his time between the U.K. and the U.S. He died of a heroin/morphine overdose in Hollywood, California on December 29, 1980, at the age of 39, virtually forgotten by the public. His only apparent legacy was his songs that others performed, until a tribute album in 2013 revived interest in the man behind the songs.

Members of Tim Hardin’s Woodstock band continue to perform. Steve “Muruga” Booker continues to drum with various artists. Gilles Malkine lives in Woodstock, New York, and is an actor, guitarist, artist, writer, disability advocate, illustrator, cartoonist, and composer. Glen Moore and Ralph Towner, bassist and guitarist, respectively, founded the jazz/world music group Oregon and remain active studio musicians. Cellist Richard Bock continued to play for some time and is now owner and operator of Giuseppe’s restaurant in Phoenix, Arizona. Pianist Bill Chelf is a session musician playing a wide range of musical styles from jazz to country rock and currently performs “hypnotic-ambient-space music.”

—Wade Lawrence & Scott Parker