Veterans at the 1969 Woodstock Festival:

How Military Service Shaped the Musicians Who Played the Peace Festival

Written by Colleen Kane

While Woodstock is practically synonymous with peace and anti-war sentiment was common, the festival’s audience included many veterans of the armed forces. Likewise, Woodstock’s musical lineup featured numerous military veterans on stage throughout the three-plus days, and at least one musician who had to leave Woodstock to attend reserve training. In fact, that’s why his band, Sweetwater, was the first band scheduled.

with Fred Hererra and Nancy Nevins of

Sweetwater, 2019

Sweetwater keyboardist Alex del Zoppo joined the Air Force Reserves to avoid the draft. He had two weeks of training starting early on August 17th, 1969. Sweetwater’s singer Nancy Nevins recalled their tight Woodstock turnaround in an interview with Bethel Woods. “Now the only reason we went on first was Alex. Because we figured that If we played first, we could get back to L.A. He had an Air Force reserve meeting in Riverside, California at 6 in the morning [Sunday], and we had to get him back.” After their set, she said they spent hours going up and down the hill trying to get a helicopter. “Finally, we got the very last one. But the pilot went up and ran out of gas. But he landed it- He knew about a little airport. It was a one-runway [local] airport. And we spent the night in that f*cking helicopter because he wouldn’t let us spend the night in the hangar. The two guys went home. The pilot and his buddy who ran the hangar. They said the guy with the key is gone. He won’t be back til morning. So we couldn’t get any gas. We just slept in the helicopter.”

“I spent a sleepless night in the chopper, knowing that I’d never get to California by six the next morning. I had visions of my own demise in ’Nam,” Del Zoppo wrote in the book Music Horror Stories.

As they tried to sleep, they heard sounds in the woods of what Nevins described as “happy hippies in the woods making their way to Woodstock. ‘Oh, we’re going to Woodstock, what fun, wheee’...Meanwhile, the roadie had an atlas and studied it. He went around the building with a flashlight and the atlas. And Freddie went around the other building after collecting all of our change. And so he made ‘help help’ phone calls from the payphones. Finally, someone showed up to get us. And they had a big Chevrolet with big fenders. Maybe it wasn’t a Chevrolet, but It looked like a chariot as far as I was concerned. And they took us back to the hotel Holiday Inn. Where by the time we got there we were persona non grata. Because the flute player [Albert Moore] had run the U-Haul into the awning of the Holiday Inn and busted it. So we were bad news, Sweetwater was bad news. We couldn’t wait to get out of there. And all the way home to Los Angeles, not a word was spoken. Not a word was spoken.”

Alex, Fred Hererra, and Nancy drove back to the city airport and flew. “Alex ended up; he actually made it. He was a little bit late [laughs] to the Air Force Reserve, and they were kinda mad about it, but I think once he told them what we’d done, he redeemed himself. Fred and I went to our parents’ houses, took showers, ate dinner, and watched the late-night news, where Woodstock was the biggest thing that had ever happened. We thought, ‘We were there? Oh my God.’ So it was weird all around.” Nancy was involved with launching a foundation and club for veterans at the college where she works, and said “I’m kinda proud of that.”

“As a very young person, I was right in the crosshairs, you might say, and I eventually got my draft notice, just like so many other folks,” John Fogerty of Creedence Clearwater Revival recalled to Military.com. “It actually says, just like in the movies, ‘Greetings from the President of the United States.’ I managed to get into an Army Reserve unit after receiving my draft notice and served my time.”

Fogerty is a longtime supporter of veterans’ causes, including Veterans Village, now called SHARE Village Las Vegas. SHARE Village is a converted motel housing over 500 families with transitional and permanent affordable rental housing, and the organization provides a bank of food and supplies to the community. In 2019 he dedicated the "Proud Mary John Fogerty Container Home" at the village, a prototype providing housing for a veteran in a converted shipping container. Another member of Creedence Clearwater Revival, drummer Doug “Cosmo” Clifford, was also called to duty in 1966 and served in the Coast Guard.

Countainer Home

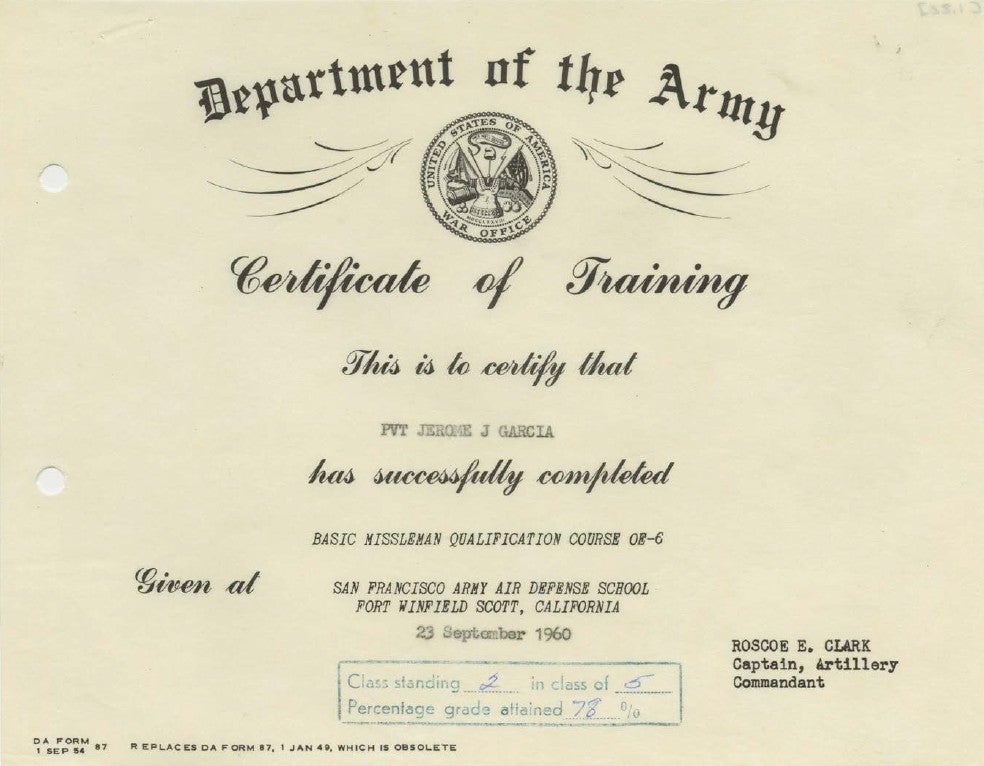

Eighteen year-old Recruit Jerome J. Garcia, later of the Grateful Dead, did not have what it takes for the U.S. Army. In 1960 he got signed up as a punishment for stealing his mother’s car, then spent less than a year before getting a general discharge. His personnel report cites “character and behavior disorders, defective attitude, substandard soldiering qualities and duty performance; and unwillingness to accept authority, discipline or responsibility,” with dishonorable mention made about his “personal uncleanliness and the filthy condition of his personal billeting area in the barracks.” A letter in his file concludes that his elimination from the service “is in the very best interests of the United States Army.”

When he performed at Woodstock at age 27, Country Joe McDonald was already an honorably discharged veteran of the U.S. Navy whose parents were members of the American Communist Party. “Both these experiences left me feeling victimized,” wrote McDonald. “I had no love for the leaders of the American military or of the American Left, but I also was not mystified by either entity. I felt a deep camaraderie and respect for the rank and file of both organizations, but I had a healthy knowledge of the capacity of both for betrayal and friendly fire...A life mission did, however, emerge from these experiences that I never was to abandon: to protect those who cannot defend themselves and to remain dedicated to the cause of justice and the dream of peace.” He began working to help Vietnam veterans secure benefit programs in 1981, starting a journey that eventually led to the dedication of the Berkeley Vietnam Veterans Memorial in 1995.

McDonald said that at first, he forgot that he was also a veteran, and speaking with a veterans counselor helped him realize that his efforts from 1959 to 1962 had helped the Vietnam war effort, and to ease his sense of guilt. He became very active in veterans’ affairs.

Joe McDonald extensively documented his path to the memorial, exhibits and events he took part in, and the electronic memorial to fallen Vietnam veterans of Berkeley that he organized, and more veteran efforts on his website.

“At times I have resisted my connection to the Vietnam War. It has been consistently bad for business, and many of my peers have cautioned and warned me about constantly bringing up the Vietnam War in my songs and in my talks to my audience. Over the years I have accepted this as my fate. I sang the song "I Feel Like I'm Fixin' to Die Rag" at Woodstock. I also sang at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on Veterans Day 1992, the tenth anniversary of the Wall, because of forces beyond my control. Both performances occurred because I happened to be there as a spectator and was asked to fill in for others! Whether or not I chose to make Vietnam a focus of my life, it seems to have chosen me.”

James Marshall Hendrix enlisted in the 101st Airborne Division of the U.S. Army on May 31st, 1961. At 19, he’d been caught twice in four days riding in stolen cars, and given the choice of two years in prison or joining the army, Jimi chose the latter.

Private Hendrix quickly earned his parachutist badge, but he was not cut out for the military. “Among his many faults, he slept while on duty, required constant supervision and wasn't a particularly good marksman,” reported Military.com. “He was a ‘habitual offender’ when it came to missing midnight bed checks and was unable to ‘carry on an intelligent conversation.’”

Jimi formed a band that played weekend gigs, and this did not go over well either. A commanding officer said, "This is one of his faults, because his mind apparently cannot function while performing duties and thinking about his guitar." According to one regimental historian, Jimi claimed to have homosexual tendencies in hopes of being released from service. His captain made a case for him to be discharged and an alleged ankle injury made it an honorable discharge.

When author Nick Chiarkas recently wrote about his service as a member of Woodstock’s “Peace Force” on the Blackbird Writer’s Blog, he recalled this interaction with Jimi Hendrix:

“At some point early Monday morning...Jimi Hendrix pointed at me and said, ‘Hop Town.’ I didn’t know what he wanted, so I said, ‘What?’ and walked toward him. I was wearing my short-sleeved red Peace shirt, and the bottom of my 101st Paratrooper tattoo was showing. He pointed at it and again said, ‘Hop Town.’ Now I knew. Just about everyone at Fort Campbell who wanted a tattoo got them in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, otherwise known as Hop Town. That’s when I learned that Jimi Hendrix served as a member of the 101st Airborne Division a few years before me. Small world.”

But Jimi wasn’t the only veteran on the Woodstock stage that Monday morning: his backing band, Gypsy Sun and Rainbows included veterans Billy Cox on bass and second guitarist Larry Lee. “Man, it was strange,” Lee recalled about his Woodstock experience. “I’d only been back a few weeks and I’m on stage, and there are helicopters overhead, naked muddy people and Jimi’s guitar sounding like a chopper or an explosion. I had to shake my head to make sure I wasn’t back in ‘Nam.”