Ravi Shankar

Ravi Shankar, perhaps India’s most famous musician, popularized the sitar and classical Indian ragas in the West. He took the stage at Woodstock on Friday evening for a mesmerizing 45-minute performance just as the rain that plagued the festival was beginning.

Day One, Performer 5: Ravi Shankar

Performed Friday night, August 15, 10:00–10:45 pm

Ravi Shankar Band Members

- Ravi Shankar: sitar

- Maya Kulkarni: tamboura

- Ustad Alla Rakha: tabla

Ravi Shankar Woodstock Setlist

- Rāga Puriya-Dhanashri (Gat In Sawarital)

- Tabla Solo In Jhaptal

- Rāga Manj Kmahaj: Alap Jor, Dhun In Kaharwa Tal, Medium & Fast Gat In Teental

Born in India (still under British control) on April 7, 1920, Rabindra Shankar Chowdhury was the son of a respected lawyer/politician/statesman from East Bengal (now Bangladesh) who deserted the family and didn’t even meet his son until Ravi was eight years old. Shankar left home in his pre-teens to travel with his brother’s dance troupe and was touring the world as a dancer by the time he was 13. Acclaimed court musician Allauddin Khan joined the dance troupe as its soloist for a European tour and began teaching Shankar the sitar. By 1938, at the age of 18, Shankar had turned his back on dance to study sitar with Khan full-time.

According to the Ravi Shankar Foundation website (www.ravishankar.org), “Indian classical music is principally based on melody and rhythm, not on harmony, counterpoint, chords, modulation, and the other basics of Western classical music.” The website continues that “the tradition of Indian classical music is an oral one. It is taught directly by the guru to the disciple, rather than by the notation method used in the West. The very heart of Indian music is the rāga: the melodic form upon which the musician improvises. This framework is established by tradition and inspired by the creative spirits of master musicians.”

Rāgas are extremely difficult to explain in a few words. Though Indian music is modal in character, rāgas should not be mistaken as modes that one hears in the music of the Middle and Far Eastern countries, nor be understood to be a scale, melody per se, a composition, or a key. A rāga is a scientific, precise, subtle and aesthetic melodic form with its own peculiar ascending and descending movement consisting of either a full seven-note octave, or a series of six or five notes (or a combination of any of these) in a rising or falling structure called the Arohana and Avarohana. It is the subtle difference in the order of notes, an omission of a dissonant note, an emphasis on a particular note, the slide from one note to another, and the use of microtones together with other subtleties, that demarcate one rāga from the other. —From ravishankar.org

Ravi Shankar completed his studies in 1944 and joined the Indian People’s Theatre Association and later assumed the role of music director of All India Radio. At AIR, Shankar composed music that combined Western and classical Indian instrumentation. Hearing of the warm reception his mentor, Khan, had received in New York, Shankar left AIR in 1956 and began touring the United Kingdom, Germany, and the United States as a performer. He recorded his first album, Three Classical Rāgas, in London that same year.

Through the rest of the 1950s and early 1960s, Shankar continued to compose, record, perform, and teach. He built an international reputation, taking part in the UNESCO music festival in Paris, touring Europe, the United States, and Australia, and composing film scores. He founded the Kinnara School of Music in Mumbai in 1962.

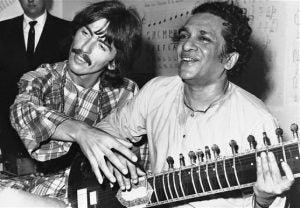

It’s uncertain whether the first Western pop group to be inspired by Ravi Shankar and use a sitar in their music was The Kinks or The Byrds, but by the mid-1960s his influence was certainly being felt. George Harrison first encountered a sitar on the set of The Beatles’ movie Help! and soon thereafter used the instrument in the song “Norwegian Wood.” Harrison sought out Shankar, sparking a lifelong friendship between the two and an international interest in classical Indian music. Before long, The Beatles, The Kinks, The Byrds, The Animals, The Rolling Stones, and even folk musician Richie Havens were all using sitars in their music.

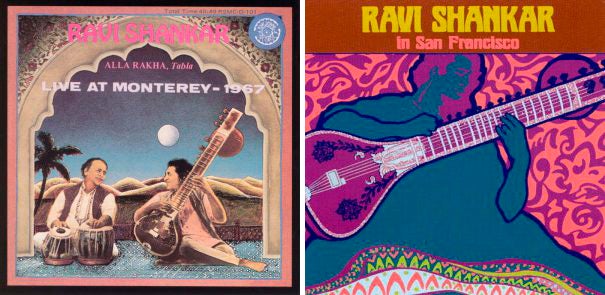

The attention also made Ravi Shankar an international superstar. He was invited to play at the Monterey International Pop Festival in 1967, and he was appointed the Buell G. Gallagher Visiting Professor at City College in New York City. His performance at Lincoln Center was called “the most ‘in’ event of the ’67 season.”

Three Ravi Shankar albums resulted from his 1967 appearance at the Monterey International Pop Festival: Live at Monterey 1967 (Beat Goes On, 1967), Ravi Shankar in San Francisco (Beat Goes On, 1967), and Ravi Shankar At Monterey International Pop Festival (One Way Records, 1967).

Given his position as a central figure in the counterculture’s appropriation of Indian culture and music, it was only natural that Ravi Shankar would be asked to play Woodstock. For this appearance, he was accompanied by Maya Kulkarni on tamboura and Ustad Alla Rakha on tabla. They sat cross-legged on a raised, carpeted platform and played a 45-minute set of classical Indian rāgas.

Unfortunately, not long after Tim Hardin and his band left the stage, the overcast sky opened up and heavy rain began to pour from the heavens, supported by heavy wind. Amazingly, panic did not ensue—the crowd, who were largely glued in place by whatever chemicals they had ingested and by the sheer number of people around them—sat calmly while buckets of water drenched them. Backstage, the scene was less relaxed. While the majority of musicians performing on Friday night played acoustic instruments and were in no immediate danger of being electrocuted, the English psychedelic folk group, The Incredible String Band held out, refusing to go onstage in the rain. The reason for this was twofold—they were now using electric pickups on their acoustic instruments, as well as an electric bass guitar. They were concerned that their instruments could be damaged in the rain, as well as the understandable concerns about mixing electricity and water. Their manager, 1960s psychedelic London heavy Joe Boyd, tried in vain to convince the String Band-ers that the time of maximum impact was nigh, but the group was having none of it. Instead, they took part in a fun jam session in the backstage pavilion and waited around to finally take to the big stage on Saturday.

One person who did not have as great a problem playing in the rain was Indian classical music maestro Ravi Shankar. With the rain whipping around the festival grounds, Shankar’s sweet sitar was just the tonic needed to calm whatever frayed nerves there were. Accompanied by Maya Kulkarni on tamboura (a drone instrument which performed a function similar to bass in Western music) and the brilliant Allah Rakha on tabla, Shankar began with the lengthy “Rāga Puriya-Dhanashri,” giving careful explanations of the mechanics of the piece to the audience at the outset. This was followed by an extended tabla solo by Allah Rakha before the musicians wound up with an intense evening rāga, “Rāga Manj Khamaj.” The interplay between Shankar and Rakha built in intensity, the pace getting faster and faster until the musicians were enveloped in a swirling musical storm of their own design. The audience roared its appreciation as they left, and John Morris gave credit to “a gentleman who played through the rain, who just kept playing.”

Although Shankar was not enamored of the “hippie scene,” he quickly acquired legendary status within the counterculture. Shankar appreciated the attention, but he grew tired of the association of his music with the hippies’ inclination to get high as a means of attaining spiritual enlightenment. “It makes me feel rather hurt when I see the association of drugs with our music,” he said. “The music to us is religion. The quickest way to reach godliness is through music. I don’t like the association of one bad thing with the music.” In a 1985 interview, Shankar expanded on this love-hate relationship with his young fans:

On one hand, I was lucky to have been there at a time when society was changing. And although much of the hippie movement seemed superficial, there was also a lot of sincerity in it, and a tremendous amount of energy. What disturbed me, though, was the use of drugs and the mixing of drugs with our music. And I was hurt by the idea that our classical music was treated as a fad—something that is very common in Western countries. People would come to my concerts stoned, and they would sit in the audience drinking Coke and making out with their girlfriends. I found it very humiliating, and there were many times I picked up my sitar and walked away. I tried to make young people sit properly and listen. I assured them that if they wanted to be high, I could make them feel high through the music, without drugs, if they’d only give me a chance. It was a terrible experience at the time. But you know, many of those young people still come to our concerts. They have matured, they are free from drugs and they have a better attitude. And this makes me happy that I went through all that. I have come full circle.

After Woodstock, Ravi Shankar continued to perform, but he stopped performing at festivals, preferring instead to perform in concert halls. He and his friend, George Harrison, organized The Concert for Bangladesh in 1971 and raised nearly a quarter of a million dollars for the starving people of that country. The concert ushered in a new form of proactive political activism by musicians that continues today with Farm Aid and other such events.

About his friend, George Harrison once called Ravi Shankar the “godfather of World Music.” The rising popularity of music from Africa, Asia, South America, and other “non-Western cultures” certainly owes a debt to Shankar, even if some purists in his own country take issue with his collaborations with Western artists.

Ravi Shankar was a Hindu and a devotee of the Hindu deity Hanuman. He was married for a time in the 1940s to his mentor’s daughter, and they had a son, Shubhendra Shankar, who sometimes performed with his father. He had a long-term on-again, off-again relationship with dancer Kamala Shastri from the late 1940s through 1981, during which time he also had an affair with American concert producer Sue Jones. Their daughter, singer/songwriter Norah Jones, was born in 1979. Shankar married Sukanya Rajan in 1989, and their daughter Anoushka Shankar was born in 1981. Ravi Shankar’s son Shubhendra passed away in 1992, and both of his daughters, Norah Jones and Anoushka Shankar, have successful musical careers.

According to The New York Times, Ravi Shankar’s “interactions throughout his career with performers from various Asian and Western traditions—including the violinist Yehudi Manuhin, the flutist Jean-Pierre Rampal, and the saxophonist and composer John Coltrane—created hybrids that opened listeners’ ears to timbres, rhythms, and tuning systems that were entirely new to them.” Ravi Shankar died in Chicago from heart disease in 2012.

Ustad Alla Rakha continued to accompany Shankar on tabla, as well as collaborating with other western musicians, such as Mickey Hart and Buddy Rich. Ustad Alla Rakha died from a heart attack in 2000. Tamboura player Maya Kulkarni is a professor and a Bharatanatyam (genre of Indian classical dance) dancer in the United States.

—Wade Lawrence & Scott Parker